I'm Gavin Mai. I love sharing what I'm learning. I'm currently based in San Juan, PR 🇵🇷

In a past life, I built models for hybrid basket-backed stablecoins, architected payment rail APIs, and developed decentralized identity solutions. Nowadays, I'm channeling my passion for technology and innovation into advising, writing, and investing in startups.

I hold a degree in Symbolic Systems from Stanford University. Outside of work, my interests include road biking, writing, bio-hacking, sustainability, consciousness research / qualia, and artificial intelligence.

In a past life, I built models for hybrid basket-backed stablecoins, architected payment rail APIs, and developed decentralized identity solutions. Nowadays, I'm channeling my passion for technology and innovation into advising, writing, and investing in startups.

I hold a degree in Symbolic Systems from Stanford University. Outside of work, my interests include road biking, writing, bio-hacking, sustainability, consciousness research / qualia, and artificial intelligence.

Latest Writings

Posted 5 months ago

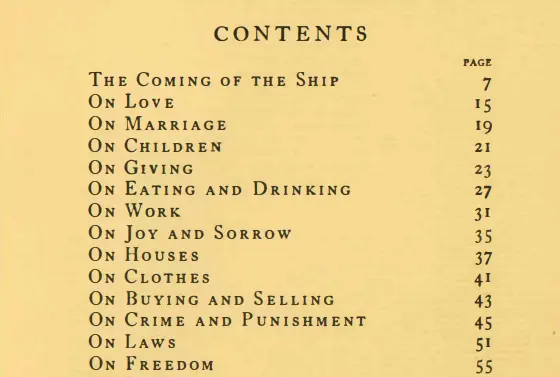

Work is Love Made Visible Career and work make up a significant part of our lives. Over a lifetime, the average person spends 13 years—roughly 90,000 hours—at work((The average person spends 90,000 hours working over their lifetime, approximately 13 years if working 40 hours/week from age 20-65. Source: Dreams.co.uk https://www.dreams.co.uk/sleep-matters-club/your-life-in-numbers-infographic)). To put this in perspective: we spend 26 years sleeping((26 years or 227,916 hours sleeping, plus another 7 years trying to fall asleep - about one-third of our entire lives. Source: Dreams.co.uk https://www.dreams.co.uk/sleep-matters-club/your-life-in-numbers-infographic)), 19 years in marriage (median duration)((The median duration of marriages in the U.S. has remained at 19 years since 2010. Source: BGSU https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/payne-median-duration-marriages-fp-20-16.html)), and only 4 years with friends and family((People spend approximately 4 years with friends and family over their lifetime. Source: Chris Bailey https://chrisbailey.com/our-life-span-is-only-17-5-years/)). When you subtract sleep and work from our lives, we're left with merely 17.5 years of truly discretionary time((After subtracting obligatory tasks like sleep and work, we're left with as few as 17.5 years of truly discretionary time in our entire lives. Source: Chris Bailey https://chrisbailey.com/our-life-span-is-only-17-5-years/)). Work isn't just a way to pay bills; it's one of the defining pillars of human existence. https://waitbutwhy.com/2014/05/life-weeks.html Yet the stark reality is that many people, if not a silent majority, are dissatisfied with their chosen vocation. Recent surveys reveal that only 30% of workers are satisfied with their pay((Only 30% of workers say they are extremely or very satisfied with how much they're paid, with 80% citing pay hasn't kept up with cost of living increases. Source: Pew Research Center 2024 https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2024/12/10/job-satisfaction/)), just 26% feel satisfied with promotion opportunities ((About a quarter are highly satisfied with their opportunities for promotion at work, while 36% cite lack of growth opportunities as a source of job dissatisfaction. Source: Pew Research Center 2024 https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2024/12/10/job-satisfaction/)), and a staggering 71% want to change bosses((For the seventh annual survey in a row, a shocking 71% of U.S. staffers said they want to change bosses, with leadership and recognition being major factors in job dissatisfaction. Source: Conference Board 2024 https://www.conference-board.org/press/job-satisfaction-2024)). When we spend such a significant portion of our finite lives working, this dissatisfaction becomes an existential crisis. This is an excerpt from The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran (1923), which is in the public domain. You can read the complete book here. I hope it helps you along your journey and provides some additional new perspectives. Thank you to Gregg Braden for turning me onto Kahlil Gibran. Work is Love Made Visible Then a ploughman said, Speak to us of Work. And he answered, saying: You work that you may keep pace with the earth and the soul of the earth. For to be idle is to become a stranger unto the seasons, and to step out of life's procession, that marches in majesty and proud submission towards the infinite. When you work you are a flute through whose heart the whispering of the hours turns to music. Which of you would be a reed, dumb and silent, when all else sings together in unison? Always you have been told that work is a curse and labour a misfortune. But I say to you that when you work you fulfil a part of earth's furthest dream, assigned to you when that dream was born, And in keeping yourself with labour you are in truth loving life, And to love life through labour is to be intimate with life's inmost secret. But if you in your pain call birth an affliction and the support of the flesh a curse written upon your brow, then I answer that naught but the sweat of your brow shall wash away that which is written. You have been told also life is darkness, and in your weariness you echo what was said by the weary. And I say that life is indeed darkness save when there is urge, And all urge is blind save when there is knowledge, And all knowledge is vain save when there is work, And all work is empty save when there is love; And when you work with love you bind yourself to yourself, and to one another, and to God. And what is it to work with love? It is to weave the cloth with threads drawn from your heart, even as if your beloved were to wear that cloth. It is to build a house with affection, even as if your beloved were to dwell in that house. It is to sow seeds with tenderness and reap the harvest with joy, even as if your beloved were to eat the fruit. It is to charge all things you fashion with a breath of your own spirit, And to know that all the blessed dead are standing about you and watching. Work is love made visible. And if you cannot work with love but only with distaste, it is better that you should leave your work and sit at the gate of the temple and take alms of those who work with joy. For if you bake bread with indifference, you bake a bitter bread that feeds but half man's hunger. And if you grudge the crushing of the grapes, your grudge distils a poison in the wine. And if you sing though as angels, and love not the singing, you muffle man's ears to the voices of the day and the voices of the night. ~Kahlil Gibran, 1923

Career and work make up a significant part of our lives. Over a lifetime, the average person spends 13 years—roughly 90,000 hours—at work((The average person spends 90,000 hours working over their lifetime, approximately 13 years if working 40 hours/week from age 20-65. Source: Dreams.co.uk https://www.dreams.co.uk/sleep-matters-club/your-life-in-numbers-infographic)). To put this in perspective: we spend 26 years sleeping((26 years or 227,916 hours sleeping, plus another 7 years trying to fall asleep - about one-third of our entire lives. Source: Dreams.co.uk https://www.dreams.co.uk/sleep-matters-club/your-life-in-numbers-infographic)), 19 years in marriage (median duration)((The median duration of marriages in the U.S. has remained at 19 years since 2010. Source: BGSU https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/payne-median-duration-marriages-fp-20-16.html)), and only 4 years with friends and family((People spend approximately 4 years with friends and family over their lifetime. Source: Chris Bailey https://chrisbailey.com/our-life-span-is-only-17-5-years/)). When you subtract sleep and work from our lives, we're left with merely 17.5 years of truly discretionary time((After subtracting obligatory tasks like sleep and work, we're left with as few as 17.5 years of truly discretionary time in our entire lives. Source: Chris Bailey https://chrisbailey.com/our-life-span-is-only-17-5-years/)). Work isn't just a way to pay bills; it's one of the defining pillars of human existence. https://waitbutwhy.com/2014/05/life-weeks.html Yet the stark reality is that many people, if not a silent majority, are dissatisfied with their chosen vocation. Recent surveys reveal that only 30% of workers are satisfied with their pay((Only 30% of workers say they are extremely or very satisfied with how much they're paid, with 80% citing pay hasn't kept up with cost of living increases. Source: Pew Research Center 2024 https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2024/12/10/job-satisfaction/)), just 26% feel satisfied with promotion opportunities ((About a quarter are highly satisfied with their opportunities for promotion at work, while 36% cite lack of growth opportunities as a source of job dissatisfaction. Source: Pew Research Center 2024 https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2024/12/10/job-satisfaction/)), and a staggering 71% want to change bosses((For the seventh annual survey in a row, a shocking 71% of U.S. staffers said they want to change bosses, with leadership and recognition being major factors in job dissatisfaction. Source: Conference Board 2024 https://www.conference-board.org/press/job-satisfaction-2024)). When we spend such a significant portion of our finite lives working, this dissatisfaction becomes an existential crisis. This is an excerpt from The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran (1923), which is in the public domain. You can read the complete book here. I hope it helps you along your journey and provides some additional new perspectives. Thank you to Gregg Braden for turning me onto Kahlil Gibran. Work is Love Made Visible Then a ploughman said, Speak to us of Work. And he answered, saying: You work that you may keep pace with the earth and the soul of the earth. For to be idle is to become a stranger unto the seasons, and to step out of life's procession, that marches in majesty and proud submission towards the infinite. When you work you are a flute through whose heart the whispering of the hours turns to music. Which of you would be a reed, dumb and silent, when all else sings together in unison? Always you have been told that work is a curse and labour a misfortune. But I say to you that when you work you fulfil a part of earth's furthest dream, assigned to you when that dream was born, And in keeping yourself with labour you are in truth loving life, And to love life through labour is to be intimate with life's inmost secret. But if you in your pain call birth an affliction and the support of the flesh a curse written upon your brow, then I answer that naught but the sweat of your brow shall wash away that which is written. You have been told also life is darkness, and in your weariness you echo what was said by the weary. And I say that life is indeed darkness save when there is urge, And all urge is blind save when there is knowledge, And all knowledge is vain save when there is work, And all work is empty save when there is love; And when you work with love you bind yourself to yourself, and to one another, and to God. And what is it to work with love? It is to weave the cloth with threads drawn from your heart, even as if your beloved were to wear that cloth. It is to build a house with affection, even as if your beloved were to dwell in that house. It is to sow seeds with tenderness and reap the harvest with joy, even as if your beloved were to eat the fruit. It is to charge all things you fashion with a breath of your own spirit, And to know that all the blessed dead are standing about you and watching. Work is love made visible. And if you cannot work with love but only with distaste, it is better that you should leave your work and sit at the gate of the temple and take alms of those who work with joy. For if you bake bread with indifference, you bake a bitter bread that feeds but half man's hunger. And if you grudge the crushing of the grapes, your grudge distils a poison in the wine. And if you sing though as angels, and love not the singing, you muffle man's ears to the voices of the day and the voices of the night. ~Kahlil Gibran, 1923Posted 5 months ago

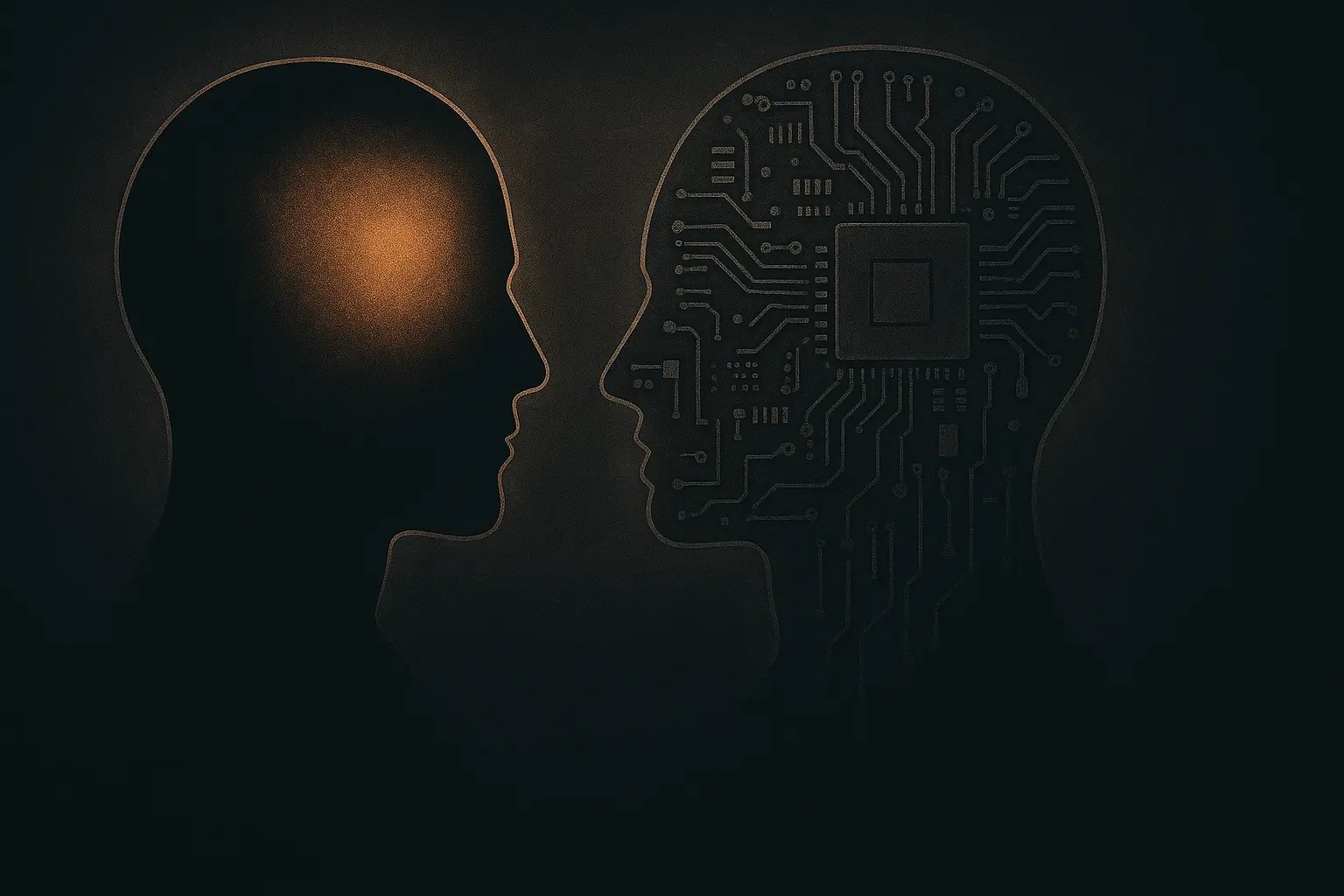

Soulless Technology I can't get no satisfaction — The Rolling Stones, 1965 We're uniquely obsessed with progress. No other species seems so relentlessly dissatisfied. Horses and carriages? Old. Cassette tapes? Bulky. Landlines? Not mobile enough. We've been this way since we first chipped flint into blades, tamed fire despite its danger, painted stories on cave walls while survival itself hung in the balance. https://www.youtube.com/embed/nrIPxlFzDi0 Are we alone in this compulsion? Unlikely. Across the cosmos, across deep time, surely others have walked this path. The universe is too vast, too old, for us to be unique. Yet look at what our progress has wrought. We have the richest economy in human history((Global GDP reached $100 trillion in 2022, yet wealth inequality has reached unprecedented levels - the 10 richest countries have per-capita purchasing power of $118,000 while the 10 poorest have just $1,600. Source: IMF https://gfmag.com/data/richest-countries-in-the-world/)), but record depression((5.7% of adults globally suffer from depression, with over 1 billion people living with mental health disorders - a 25% increase since COVID-19. Source: WHO https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression)) and homelessness((In the U.S. alone, 771,480 people experienced homelessness in January 2024 - the highest number since data collection began, an 18% increase from 2023. Source: HUD https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2024-AHAR-Part-1.pdf)). Modern medicine saves millions from ancient killers, while obesity((40.3% of U.S. adults have obesity in 2024; obesity causes 3.7 million deaths annually from chronic diseases worldwide. Sources: CDC https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db508.htm and WHO https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight)), inflammation, and heart disease run rampant. The internet connects eight billion humans, yet loneliness reaches epidemic proportions((24% of people globally experience regular loneliness; 30% of U.S. adults feel lonely at least weekly, with young adults hit hardest at 79%. Sources: WHO https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/demographic-change-and-healthy-ageing/social-isolation-and-loneliness and APA https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/new-apa-poll-one-in-three-americans-feels-lonely-e)). Real community feels like a relic. These aren't just unfortunate side effects or growing pains. They reveal a pattern: when we build without asking why, when we innovate just to innovate or profit just to profit, our tools amplify problems rather than solve them. We've mastered how to build but forgotten to ask what's worth building. This forgetting points to something fundamental we've lost: consciousness. From the Latin "conscientia," meaning "knowing with," consciousness implies self-awareness, wisdom, connection. Our ability to produce technology has far outpaced this deeper knowing. Consider our relationship with Earth. We have one planet, perfectly positioned in the cosmos, neither too hot nor too cold for life to flourish. A gossamer-thin ozone layer protects us from radiation while trapping just enough heat. We're blessed with oxygen, water, and rainforests that form a living system of staggering complexity and fragility. If honey bees vanished tomorrow, three-quarters of our food crops would lose their pollinators((75% of major food crops depend on pollinators. Of the 100 crops that provide 90% of the world's food, 71 are pollinated by bees. Colony losses reached 62% in 2024-2025, the worst ever recorded. Sources: UN FAO https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/Declining-bee-populations-pose-threat-to-global-food-security-and-nutrition/en and Penn State https://www.psu.edu/impact/story/protecting-pollinators/)). No more apples, almonds, or avocados. No coffee or chocolate. We'd survive on wheat and rice, but the diverse, nutritious foods that make life worth living would vanish. Everything hangs by such delicate threads. Yet we poison the air, contaminate the water, bury our waste, and excavate caverns for nuclear refuse((Air pollution causes 8.1 million deaths annually, the second leading risk factor for death globally. 2.2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, with 44% of wastewater returning untreated to the environment. Nuclear waste sites like Hanford contain 56 million gallons of radioactive material, costing over $100 billion to clean. Sources: State of Global Air 2024 https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources/report/state-global-air-report-2024 and UNICEF https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/air-pollution-accounted-81-million-deaths-globally-2021-becoming-second-leading-risk)). We treat our only home like it's disposable. Profit today, let tomorrow's children clean up the mess. But if each generation thinks this way, eventually there's no tomorrow left. We approach our own Rubicon, a point of no return where the damage becomes irreversible. Not just for us, but for every species that shares this planet. The paradoxes are starkest in our digital lives. Social media promised connection; it delivered isolation. We have thousands of "friends" but no one to call in crisis. We doom scroll for hours, losing three days each month to our screens((31% of American adults doom scroll regularly, with rates reaching 51% among Gen Z. The average person spends 6 hours daily consuming media and believes they lose 3 days monthly to scrolling. Source: 2024 Talker Research https://www.livenowfox.com/news/talker-research-media-consumption-report-2024)). Meta's latest offering, Vibes, floods feeds with AI-generated video slop designed purely to hook attention and serve ads((Meta launched Vibes on September 25, 2025, a feed of entirely AI-generated videos. Users responded to Zuckerberg's announcement with "gang nobody wants this" and "Bro's posting ai slop on his own app." Source: Meta https://about.fb.com/news/2025/09/introducing-vibes-ai-videos/)). gang nobody wants this— s (@sdw) September 25, 2025 Public backlash against tech billionaires pushing AI slop - selling digital cigarettes to the masses All this engineered addiction serves one purpose: consumption. https://www.youtube.com/embed/PgU71nWCNeY "We buy things we don't need with money we don't have to impress people we don't like." — Fight Club Echo chambers amplify division. Outrage travels faster than understanding. We carry all human knowledge in our pockets, yet drown in misinformation. Conspiracy theories spread six times faster than truth. Deepfakes blur reality. Algorithms amplify extremism over wisdom. The information age has become the confusion age. Artificial intelligence is the ultimate expression of this disconnect. We rush to automate everything, supposedly to create abundance, but really just to cut costs and maximize profits. Yet what's the endgame? When everyone uses AI, competitive advantage evaporates. Margins collapse to the cost of electricity and API fees. We're racing to the bottom, automating ourselves into irrelevance. Helena Blavatsky warned in the 19th century of "soulless" beings, entities that mimic intelligence without consciousness. Now we hand healthcare, justice, and creativity to machines that don't know what any of it means. And for what? This relentless efficiency doesn't create the abundance we're promised. Instead we get social credit scores that turn citizens into prisoners. Autonomous drones that make killing as easy as clicking a mouse. Deepfakes that obliterate any notion of truth. AI slop flooding every feed, every platform, optimizing for engagement while draining all meaning from human expression. Black Mirror looks quaint compared to what's already here. The dystopia isn't coming. We're building it, one algorithm at a time. The economic paradoxes are equally stark. California's economy alone would rank 5th globally, yet tent cities sprawl beneath Silicon Valley offices where twenty-somethings make $300k. New York generates more wealth than entire nations while families sleep in subway stations. We can 3D print houses in days but "can't afford" to shelter humans. Apps deliver sushi in 15 minutes to those who pay $3000/month for studios, while food banks run empty miles away. Tent cities in the shadow of billion-dollar tech campuses - the paradox of modern prosperity This isn't just market failure. It's what happens when central banks print trillions, inflating assets for those who own them while wages stagnate for everyone else. As Richard Werner documented in Princes of the Yen, credit creation concentrates wealth by design, not accident. Technology amplifies these distortions. AI won't fix what consciousness hasn't addressed: we have all the tools to solve homelessness, hunger, and basic human needs. We choose not to. We'd rather optimize ad clicks than optimize human flourishing. The American Dream priced out - housing costs soar while incomes stagnate Technology doesn't solve inequality; it amplifies it. Like money revealing character rather than changing it, technology magnifies what's already there. How we build anything reveals how we build everything. Those with capital use AI to generate more wealth. Those without fall further behind. Educational technology widens the gap between connected and disconnected students. The gig economy delivers precarity disguised as flexibility. The pattern is consistent: our tools mirror our values, and our values prioritize extraction over care. So where does it all go? Technology and consciousness are parallel tracks of human evolution. The relationship between them determines our fate. When innovation exceeds wisdom, we get dystopia. Nuclear energy becomes nuclear weapons. Surveillance becomes oppression. Algorithms become manipulation. When technology leads and consciousness lags, we get Orwell's 1984 as reality. China's social credit system scores humanity rather than serves it. Facial recognition turns public spaces into open-air prisons. Predictive policing criminalizes poverty. Digital currencies could become tools for total economic control. The technocratic dream of efficiency becomes a nightmare of dehumanization. https://www.youtube.com/embed/a9sn4_Dpa00 This is the path of "might makes right," where those who control the technology control everyone else. Tech billionaires speak of humanity as a problem to be solved rather than a miracle to be cherished. Universal basic income proposals sound benevolent but could become digital breadlines, keeping the masses barely sustained while a technological elite accumulates unimaginable power. AI systems already make decisions about human lives: who gets hired, who gets loans, who gets released from prison. These systems have no genuine understanding of what it means to be human. When technology becomes the answer to everything, it devolves into pure materialism. Soulless, mechanical, dead. Everything optimized but nothing has meaning. Infinite entertainment but no joy. Constantly connected but never truly together. We can simulate any experience but lose touch with reality itself. But there's another path, one we keep avoiding because it requires something harder than building machines: growing up. The answer doesn't lie in AGI or ASI or whatever acronym comes next. We keep hoping the next technological leap will magically solve problems that aren't technological at their core. Loneliness isn't a software bug. Inequality isn't a hardware limitation. Environmental collapse isn't an optimization problem. What we need isn't more processing power but more compassion. Not faster algorithms but deeper wisdom. Not virtual connections but real community. We need to remember what every indigenous culture knew: harming the Earth harms ourselves. We are not separate from nature, we are nature. The bees dying are us dying. The oceans acidifying are our blood turning poison. This isn't mysticism. It's the most practical truth there is. Every living system is interconnected. Damage one part, damage the whole. Yet we treat Earth like a platform to be exploited rather than a living system we're part of. We treat each other as competitors rather than collaborators in survival. The real evolution we need isn't technological but spiritual. Not in some religious sense, but in recognizing our fundamental interconnection. When you truly understand that your wellbeing depends on everyone else's wellbeing, you stop hoarding and start sharing. When you grasp that Earth's health is your health, you stop poisoning and start healing. This shift in consciousness could transform technology from a weapon into a gift. Imagine AI serving genuine human needs rather than manufactured desires. Automation creating leisure rather than unemployment. Networks building understanding rather than division. We have all the tools needed to create something approaching heaven on Earth. What we lack is the maturity to use them. But maturity can't be downloaded or coded. It must be earned through facing hard truths: that our current path leads to extinction. That infinite growth on a finite planet is suicide. That no amount of technology will save us if we don't save ourselves first. The choice is stark. Continue our adolescent fantasy that more technology equals more happiness, and watch everything collapse. Or grow up. Develop the consciousness to match our capabilities. Learn to love the world and each other before it's too late. Time is running out. Climate tipping points approach. AI systems grow beyond our control. Social fabric tears. The question isn't whether technology will advance. It will. The question is whether we'll advance with it, or let it drag us into a soulless future where everything is optimized except what matters: love, meaning, connection, life itself. The ultimate purpose of technology will be whatever we choose, or whatever we allow to be chosen for us. But first, we need to become conscious enough to choose wisely. The alternative is extinction. A final lesson for a species that could build anything except wisdom.

I can't get no satisfaction — The Rolling Stones, 1965 We're uniquely obsessed with progress. No other species seems so relentlessly dissatisfied. Horses and carriages? Old. Cassette tapes? Bulky. Landlines? Not mobile enough. We've been this way since we first chipped flint into blades, tamed fire despite its danger, painted stories on cave walls while survival itself hung in the balance. https://www.youtube.com/embed/nrIPxlFzDi0 Are we alone in this compulsion? Unlikely. Across the cosmos, across deep time, surely others have walked this path. The universe is too vast, too old, for us to be unique. Yet look at what our progress has wrought. We have the richest economy in human history((Global GDP reached $100 trillion in 2022, yet wealth inequality has reached unprecedented levels - the 10 richest countries have per-capita purchasing power of $118,000 while the 10 poorest have just $1,600. Source: IMF https://gfmag.com/data/richest-countries-in-the-world/)), but record depression((5.7% of adults globally suffer from depression, with over 1 billion people living with mental health disorders - a 25% increase since COVID-19. Source: WHO https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression)) and homelessness((In the U.S. alone, 771,480 people experienced homelessness in January 2024 - the highest number since data collection began, an 18% increase from 2023. Source: HUD https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2024-AHAR-Part-1.pdf)). Modern medicine saves millions from ancient killers, while obesity((40.3% of U.S. adults have obesity in 2024; obesity causes 3.7 million deaths annually from chronic diseases worldwide. Sources: CDC https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db508.htm and WHO https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight)), inflammation, and heart disease run rampant. The internet connects eight billion humans, yet loneliness reaches epidemic proportions((24% of people globally experience regular loneliness; 30% of U.S. adults feel lonely at least weekly, with young adults hit hardest at 79%. Sources: WHO https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/demographic-change-and-healthy-ageing/social-isolation-and-loneliness and APA https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/new-apa-poll-one-in-three-americans-feels-lonely-e)). Real community feels like a relic. These aren't just unfortunate side effects or growing pains. They reveal a pattern: when we build without asking why, when we innovate just to innovate or profit just to profit, our tools amplify problems rather than solve them. We've mastered how to build but forgotten to ask what's worth building. This forgetting points to something fundamental we've lost: consciousness. From the Latin "conscientia," meaning "knowing with," consciousness implies self-awareness, wisdom, connection. Our ability to produce technology has far outpaced this deeper knowing. Consider our relationship with Earth. We have one planet, perfectly positioned in the cosmos, neither too hot nor too cold for life to flourish. A gossamer-thin ozone layer protects us from radiation while trapping just enough heat. We're blessed with oxygen, water, and rainforests that form a living system of staggering complexity and fragility. If honey bees vanished tomorrow, three-quarters of our food crops would lose their pollinators((75% of major food crops depend on pollinators. Of the 100 crops that provide 90% of the world's food, 71 are pollinated by bees. Colony losses reached 62% in 2024-2025, the worst ever recorded. Sources: UN FAO https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/Declining-bee-populations-pose-threat-to-global-food-security-and-nutrition/en and Penn State https://www.psu.edu/impact/story/protecting-pollinators/)). No more apples, almonds, or avocados. No coffee or chocolate. We'd survive on wheat and rice, but the diverse, nutritious foods that make life worth living would vanish. Everything hangs by such delicate threads. Yet we poison the air, contaminate the water, bury our waste, and excavate caverns for nuclear refuse((Air pollution causes 8.1 million deaths annually, the second leading risk factor for death globally. 2.2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, with 44% of wastewater returning untreated to the environment. Nuclear waste sites like Hanford contain 56 million gallons of radioactive material, costing over $100 billion to clean. Sources: State of Global Air 2024 https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources/report/state-global-air-report-2024 and UNICEF https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/air-pollution-accounted-81-million-deaths-globally-2021-becoming-second-leading-risk)). We treat our only home like it's disposable. Profit today, let tomorrow's children clean up the mess. But if each generation thinks this way, eventually there's no tomorrow left. We approach our own Rubicon, a point of no return where the damage becomes irreversible. Not just for us, but for every species that shares this planet. The paradoxes are starkest in our digital lives. Social media promised connection; it delivered isolation. We have thousands of "friends" but no one to call in crisis. We doom scroll for hours, losing three days each month to our screens((31% of American adults doom scroll regularly, with rates reaching 51% among Gen Z. The average person spends 6 hours daily consuming media and believes they lose 3 days monthly to scrolling. Source: 2024 Talker Research https://www.livenowfox.com/news/talker-research-media-consumption-report-2024)). Meta's latest offering, Vibes, floods feeds with AI-generated video slop designed purely to hook attention and serve ads((Meta launched Vibes on September 25, 2025, a feed of entirely AI-generated videos. Users responded to Zuckerberg's announcement with "gang nobody wants this" and "Bro's posting ai slop on his own app." Source: Meta https://about.fb.com/news/2025/09/introducing-vibes-ai-videos/)). gang nobody wants this— s (@sdw) September 25, 2025 Public backlash against tech billionaires pushing AI slop - selling digital cigarettes to the masses All this engineered addiction serves one purpose: consumption. https://www.youtube.com/embed/PgU71nWCNeY "We buy things we don't need with money we don't have to impress people we don't like." — Fight Club Echo chambers amplify division. Outrage travels faster than understanding. We carry all human knowledge in our pockets, yet drown in misinformation. Conspiracy theories spread six times faster than truth. Deepfakes blur reality. Algorithms amplify extremism over wisdom. The information age has become the confusion age. Artificial intelligence is the ultimate expression of this disconnect. We rush to automate everything, supposedly to create abundance, but really just to cut costs and maximize profits. Yet what's the endgame? When everyone uses AI, competitive advantage evaporates. Margins collapse to the cost of electricity and API fees. We're racing to the bottom, automating ourselves into irrelevance. Helena Blavatsky warned in the 19th century of "soulless" beings, entities that mimic intelligence without consciousness. Now we hand healthcare, justice, and creativity to machines that don't know what any of it means. And for what? This relentless efficiency doesn't create the abundance we're promised. Instead we get social credit scores that turn citizens into prisoners. Autonomous drones that make killing as easy as clicking a mouse. Deepfakes that obliterate any notion of truth. AI slop flooding every feed, every platform, optimizing for engagement while draining all meaning from human expression. Black Mirror looks quaint compared to what's already here. The dystopia isn't coming. We're building it, one algorithm at a time. The economic paradoxes are equally stark. California's economy alone would rank 5th globally, yet tent cities sprawl beneath Silicon Valley offices where twenty-somethings make $300k. New York generates more wealth than entire nations while families sleep in subway stations. We can 3D print houses in days but "can't afford" to shelter humans. Apps deliver sushi in 15 minutes to those who pay $3000/month for studios, while food banks run empty miles away. Tent cities in the shadow of billion-dollar tech campuses - the paradox of modern prosperity This isn't just market failure. It's what happens when central banks print trillions, inflating assets for those who own them while wages stagnate for everyone else. As Richard Werner documented in Princes of the Yen, credit creation concentrates wealth by design, not accident. Technology amplifies these distortions. AI won't fix what consciousness hasn't addressed: we have all the tools to solve homelessness, hunger, and basic human needs. We choose not to. We'd rather optimize ad clicks than optimize human flourishing. The American Dream priced out - housing costs soar while incomes stagnate Technology doesn't solve inequality; it amplifies it. Like money revealing character rather than changing it, technology magnifies what's already there. How we build anything reveals how we build everything. Those with capital use AI to generate more wealth. Those without fall further behind. Educational technology widens the gap between connected and disconnected students. The gig economy delivers precarity disguised as flexibility. The pattern is consistent: our tools mirror our values, and our values prioritize extraction over care. So where does it all go? Technology and consciousness are parallel tracks of human evolution. The relationship between them determines our fate. When innovation exceeds wisdom, we get dystopia. Nuclear energy becomes nuclear weapons. Surveillance becomes oppression. Algorithms become manipulation. When technology leads and consciousness lags, we get Orwell's 1984 as reality. China's social credit system scores humanity rather than serves it. Facial recognition turns public spaces into open-air prisons. Predictive policing criminalizes poverty. Digital currencies could become tools for total economic control. The technocratic dream of efficiency becomes a nightmare of dehumanization. https://www.youtube.com/embed/a9sn4_Dpa00 This is the path of "might makes right," where those who control the technology control everyone else. Tech billionaires speak of humanity as a problem to be solved rather than a miracle to be cherished. Universal basic income proposals sound benevolent but could become digital breadlines, keeping the masses barely sustained while a technological elite accumulates unimaginable power. AI systems already make decisions about human lives: who gets hired, who gets loans, who gets released from prison. These systems have no genuine understanding of what it means to be human. When technology becomes the answer to everything, it devolves into pure materialism. Soulless, mechanical, dead. Everything optimized but nothing has meaning. Infinite entertainment but no joy. Constantly connected but never truly together. We can simulate any experience but lose touch with reality itself. But there's another path, one we keep avoiding because it requires something harder than building machines: growing up. The answer doesn't lie in AGI or ASI or whatever acronym comes next. We keep hoping the next technological leap will magically solve problems that aren't technological at their core. Loneliness isn't a software bug. Inequality isn't a hardware limitation. Environmental collapse isn't an optimization problem. What we need isn't more processing power but more compassion. Not faster algorithms but deeper wisdom. Not virtual connections but real community. We need to remember what every indigenous culture knew: harming the Earth harms ourselves. We are not separate from nature, we are nature. The bees dying are us dying. The oceans acidifying are our blood turning poison. This isn't mysticism. It's the most practical truth there is. Every living system is interconnected. Damage one part, damage the whole. Yet we treat Earth like a platform to be exploited rather than a living system we're part of. We treat each other as competitors rather than collaborators in survival. The real evolution we need isn't technological but spiritual. Not in some religious sense, but in recognizing our fundamental interconnection. When you truly understand that your wellbeing depends on everyone else's wellbeing, you stop hoarding and start sharing. When you grasp that Earth's health is your health, you stop poisoning and start healing. This shift in consciousness could transform technology from a weapon into a gift. Imagine AI serving genuine human needs rather than manufactured desires. Automation creating leisure rather than unemployment. Networks building understanding rather than division. We have all the tools needed to create something approaching heaven on Earth. What we lack is the maturity to use them. But maturity can't be downloaded or coded. It must be earned through facing hard truths: that our current path leads to extinction. That infinite growth on a finite planet is suicide. That no amount of technology will save us if we don't save ourselves first. The choice is stark. Continue our adolescent fantasy that more technology equals more happiness, and watch everything collapse. Or grow up. Develop the consciousness to match our capabilities. Learn to love the world and each other before it's too late. Time is running out. Climate tipping points approach. AI systems grow beyond our control. Social fabric tears. The question isn't whether technology will advance. It will. The question is whether we'll advance with it, or let it drag us into a soulless future where everything is optimized except what matters: love, meaning, connection, life itself. The ultimate purpose of technology will be whatever we choose, or whatever we allow to be chosen for us. But first, we need to become conscious enough to choose wisely. The alternative is extinction. A final lesson for a species that could build anything except wisdom.Posted about 1 year ago

How to Build a Solar Backup System for Under $5,000 In 1752, Benjamin Franklin flew his famous kite in a thunderstorm, helping unlock the mysteries of electricity. Nearly 130 years later, Thomas Edison would illuminate the world with the first practical light bulb. Today, we rarely pause to marvel at these innovations - flipping a switch for light or plugging in a laptop has become second nature. Yet our modern comforts rest entirely on a complex and sometimes fragile power grid that we take for granted. Artistic Rendition of Ben Franklin's Kite Experiment Living in Puerto Rico, I've experienced firsthand how precious reliable electricity truly is. While the local power grid generally works well, occasional outages from storms or maintenance are stark reminders of how dependent we are on this invisible force for everything from air conditioning and refrigeration to internet connectivity and medical devices. Today, I want to share how I was able to build a home backup system (DIY) with no electrical engineering background for less than $5000, and how you can too. In 2017, Hurricane Maria - a devastating Category 5 storm with sustained winds over 155 mph - exposed just how fragile our power infrastructure really is. The entire island lost power, and for many communities, electricity wasn't restored for over 6 months. This wasn't just an inconvenience - it was a humanitarian crisis that affected everything from food storage to medical care. Hurricane Maria Weather Map The vulnerability stems from decades of neglected infrastructure. Our power grid is a patchwork of aging components, with many critical elements like transformers and transmission lines operating well beyond their intended lifespan. This fragility is compounded by geography - most of our power generation happens in the south, while the majority of the population lives in the north, requiring an extension transmission network across mountainous terrain. Puerto Rico electricity rates compared to USA (source) The cost of this inefficient system falls directly on residents. Puerto Ricans pay between $0.27 - $0.35 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) for electricity - nearly triple the US mainland average of $0.12/kWh. This high cost is driven by three main factors: Constant infrastructure repairs and maintenance Heavy reliance on imported fossil fuels, which power 95% of our grid (compared to 78% on the mainland) The Jones Act's shipping restrictions, which force Puerto Rico to use expensive U.S.-flagged vessels for fuel transport between American ports, even when cheaper international options are available. This century-old maritime law adds significant costs to nearly every shipment of fuel and equipment reaching the island Puerto Rico's power grid showing 230kV and 115kV transmission lines. Most power generation is in the south while population centers are in the north, creating infrastructure challenges. Map: Brandon Palacio (source) Even today, five years after Maria, regular outages remain a fact of life. While most last less than 24 hours, multi-day blackouts still occur several times a year, especially during hurricane seasons. These outages aren't merely inconvenient. They can be life-threatening for vulnerable residents. Many locals rely of electricity for critical medical equipment like oxygen concentrations, dialysis machines, or refrigerated medications. For them, a reliable power supply isn't a luxury-it's a necessity. The reality drove me to create this guide with two primary objectives: Document how I built a reliable, cost-effective backup power system to improve my own resilience Provide a practical blueprint for others to achieve energy independence, regardless of their technical background While I don't have formal electrical engineering training (my background is in computer science), I've done extensive research to understand the fundamentals of power systems and hope to pass those learnings to you. DISCLAIMER: This guide is for informational purposes only. Please consult with a qualified/licensed electrician in your local area before attempting any electrical work. Proceed at your own risk. Improper installation can result in serious injury or death. Every home solar backup system requires these core components: Solar Panels Copper Wire (various gauges and lengths) Inverter Transfer Switch(es) Battery Fuses While this may seem daunting if you're new to electrical systems, the basic concept is straightforward: This is a basic rendering of the essentials of any solar backup battery system. In practice, you need to add more components between systems to ensure safety, which we will cover later. Solar panels capture sunlight and convert it to direct current (DC) electricity Copper wiring creates the electrical pathways between components - from panels to inverter to battery The inverter transforms direct current (DC) into alternating current (AC) that powers your home Transfer switches integrate your solar power with your home's electrical panel Batteries store energy for use when sunlight isn't available A charge controller optimizes the solar DC voltage to efficiently charge your batteries Fuses provide critical protection against electrical surges and faults Bus Bars - These efficiently connect multiple wires together. While not required, they can reduce copper wire usage, which is increasingly expensive. Battery Monitor - Some batteries include built-in displays, but a separate monitor may be needed to track charge levels Wire Conduits - These improve aesthetics by neatly concealing wiring Battery Disconnect Switch - Allows for easy battery isolation without manually removing connections Battery monitor display showing voltage, current, and charge status Bus bar for efficiently connecting multiple wires together Wire conduit for neatly organizing and protecting cables Battery disconnect switch for safely isolating the battery system Though not essential, these additions significantly enhance system usability and maintenance while remaining relatively affordable. Let's start with the basics: how much power does your home actually need? The average US household uses about 30 kilowatt-hours (kWh) each day, but this can vary quite a bit depending on your situation. Your home likely falls into one of these categories: Low Usage (10-20 kWh/day) Perfect for small homes or apartments You probably use AC sparingly Your appliances are energy-efficient Medium Usage (20-35 kWh/day) Typical for an average single-family home You use AC/heating moderately throughout the day High Usage (35+ kWh/day) Common for larger homes You run AC/heating frequently You have extra power draws like pool pumps or multiple refrigerators Let's say you want to generate 10KWH of electricity per day – enough to run your essential appliances. Here's how to figure out what you need: First, count your daily sun hours (let's use 7 hours of good sunlight) Then, calculate your hourly needs: 10KWH ÷ 7 hours = 1.43KW per hour Finally, add some extra capacity for cloudy days Solar panels typically come in sizes from 200W to 500W. When shopping for panels, you'll want to consider: How much space you have for installation Your budget Local weather conditions Here's a money-saving tip: look at the cost per watt when comparing panels: Used panels cost around $0.20/watt (I found 250W panels for $50 each) New panels run $0.60-$0.80/watt Explanation on how solar panels work While used panels might be 10-15% less efficient, they can save you a lot of money. I recommend checking out Eco Direct for new panels, but there are many other options online. Let's look at a real example: To get that 1.43 KW/hour we calculated earlier, you could use: Eight 250W panels (like I did), or Four 500W bifacial panels if you prefer newer technology Bifacial panels are more expensive, but provide higher power density than traditional panels Once you've got your solar panels figured out, you'll need batteries to store that energy. For a system generating 10KWH daily, you'll want at least that much storage capacity – I'd recommend 10-12.5KWH to be safe. You have several battery options to consider: Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePo4) - My top recommendation Lead Acid AGM (Absorbed Glass Mat) Gel Batteries Battery Type Pros Cons Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePo4) • Longest lifespan (10-15 years)• Deep discharge capable (80-90%)• Lightweight• No maintenance required• Fast charging • Higher upfront cost• Special shipping requirements• Temperature sensitive• Requires BMS Lead Acid • Lowest upfront cost• Widely available• Simple technology• Easy to ship • Short lifespan (3-5 years)• Limited depth of discharge (50%)• Heavy• Requires maintenance• Slow charging AGM • Maintenance-free• Good shock/vibration resistance• No spill risk• Moderate lifespan (4-7 years) • Higher cost than flooded lead-acid• Limited depth of discharge (50%)• Temperature sensitive• Heavy Gel • Deep cycle capable• No spill risk• Good for extreme temperatures• Low maintenance • Expensive• Very sensitive to overcharging• Slow charging required• Special charging profile needed I prefer Lithium Iron Phosphate because they handle deep discharges better and last significantly longer. Just keep in mind that shipping these batteries requires special handling – you can't just pop them in the mail through USPS or UPS without proper documentation. If you're in Hawaii or Puerto Rico like me, you'll need freight shipping((There are many freight shipping companies that service Puerto Rico. I personally went with Crowley Logistics - https://crowley.com. They have a simple system for creating an order via email and then giving you a booking number, where you can send heavy or hazardous material like LiFePo4 batteries to an address in Jacksonville, with auto forwarding to the port of San Juan)). When storing multiple LiFePo4 batteries, proper organization is crucial for both safety and maintenance. I use a heavy-duty shelving unit rated for 250 pounds per shelf, which easily handles two 12V 200AH batteries per level (each battery weighs about 48 pounds). A sturdy shelving system keeps batteries organized and easily accessible for maintenance Key considerations for battery storage: Keep batteries elevated off the ground to prevent moisture damage Ensure proper ventilation around each battery Allow enough space for battery maintenance and terminal access Use sturdy, non-conductive shelving that can handle the weight Keep batteries at room temperature when possible Here's something crucial: for any system around 10KWH or larger, you'll want to use a 48V setup. Here's why: Remember the formula: Watts = Amps × Volts. Higher voltage means you need fewer amps to deliver the same power. This is really important because high amperage can make wires hot – sometimes dangerously hot. https://www.youtube.com/embed/FVwver30uE8 A 48V system can safely handle about 100A with 2-gauge wire, making it ideal for home backup systems. In contrast, smaller 12V or 24V systems require dangerously high amperage to deliver the same power - for example, a 4800W load would need 400A at 12V versus just 100A at 48V. When selecting wire gauge, it's always safer to go bigger (lower gauge number) than necessary. While thicker copper wire costs more upfront, it provides better safety margins and lower resistance. Using wire that's too thin creates a serious fire hazard due to heat buildup from resistance. Some key guidelines: 2 AWG wire can handle ~100A at 48V 4 AWG wire can handle ~70A at 48V 6 AWG wire can handle ~55A at 48V If cost constraints prevent using appropriately thick wire, you can increase system voltage to reduce amperage. However, remember that any voltage conversion (like 96V to 48V through a charge controller) will increase amperage on the output side, requiring appropriate wire gauge for that section. This chart shows how many amps different wire gauges can safely handle. Always check this when planning your system! Here is a chart showing optimal wire gauge as a function of the expected amperage and length of wire. One of the most important skills for building a solar system is proper wire crimping. Poor connections can lead to voltage drops, heat buildup, or even fires. Here's what you need to know: Example of a properly crimped connection vs a poor connection Essential crimping tips: Always use the correct size lug for your wire gauge Strip the exact amount of wire insulation needed (not too much, not too little) Use a ratcheting crimper that won't release until proper pressure is applied Make two crimps per connection for extra security Gently tug test each connection Use heat shrink tubing to protect connections For this build, I recommend either: AMZCNC Hydraulic Crimper ($45) - Great for larger gauge wires (12-2/0 AWG), uses hydraulic pressure for consistent crimps iCrimp Battery Cable Tool ($34) - More compact option for 8-1/0 AWG, includes a wire cutter I personally use the AMZCNC model since it handles the full range of wire sizes needed for solar installations. The hydraulic action makes crimping large gauge wires much easier on your hands. https://www.youtube.com/embed/vaIzmZ2y5wo Understanding how to properly wire your components is critical for both safety and efficiency. Let's break down the key connections and considerations: To achieve our target 48V system voltage, we need to properly configure our 12V batteries: First, balance batteries by connecting them in parallel Then, arrange in series to reach 48V (4 x 12V batteries) Finally, connect multiple 48V groups in parallel to increase capacity Battery wiring diagram showing parallel balancing and series configuration Important: Always balance batteries in parallel first to equalize voltages. This maximizes efficiency and battery life by ensuring all cells start at the same voltage level. Here is a video that walks you through balancing your batteries. It's as simple as connecting the batteries in parallel. Make sure positive terminals are connected only to positive, and negative terminals only to negative. https://www.youtube.com/embed/oOEqnCrxPYg If you cross wires, you run the risk of shorting a battery, which is dangerous. https://www.youtube.com/embed/PqyUtQv1WoQ Expanding Capacity: To increase your battery bank capacity, you can add multiple 48V battery sets in parallel - for example, if using 12V batteries, first balance and connect groups of 4 batteries in series to create 48V, then connect multiple 48V sets in parallel to expand capacity. Here's the recommended connection sequence from batteries to inverter: Battery bank → Battery disconnect switch (master control) Disconnect switch → Class T fuse (system protection) Fuse → Bus bars (power distribution hub) Bus bars → Various components: MPPT charge controller Battery monitor Inverter Basic wiring diagram showing major component connections For maximum MPPT efficiency, configure your panels to achieve higher voltage: Target voltage should be well above battery voltage (48V) Higher voltage = better MPPT efficiency Stay within charge controller limits (250V max in my case) Use this calculator to determine optimal panel configuration for your location: Victron SmartSolar MPPT (250V/100A) charge controller with Bluetooth monitoring capabilities I chose the Victron SmartSolar 250V/100A MPPT controller for several reasons: High voltage capacity (250V) allows flexible panel configuration Quality brand with excellent reliability Built-in Bluetooth monitoring Efficient MPPT algorithms While Victron is premium-priced, more economical options exist from brands like: Renogy EPEver MidNite Solar Victron SmartShunt 500A / 50mV - Bluetooth Battery Shunt Adding a battery monitor is crucial for system management. The Victron Smart Battery Monitor: Installs inline at the bus bar Connects to charge controller via Bluetooth Provides real-time system stats: Battery voltage Current draw State of charge Power consumption history From the bus bars, power flows to: Inverter (48V DC → 120V/240V AC) Transfer switches (grid vs backup power selection) Home electrical panel Individual circuits/appliances Always ensure proper fusing and wire gauge selection based on maximum current: 100A system → 2 AWG wire minimum Add appropriate fuses at each major connection Use proper crimping techniques for all terminals My complete system cost $7,109.07, but you can build a similar setup for under $5,000. The system is modular by design - I chose to build a larger 20KWH system with premium components, but you can start with a 10KWH system (using 4 batteries instead of 8) and skip the solar panel stands to save about $2,456 total: Reducing from 8 to 4 batteries saves $1,400 (4 × $350) Skipping solar panel stands saves $1,056 Each additional 2.5KWH of battery capacity costs around $350, making it easy to expand later. Let's break down the core components that typically account for 70-80% of your investment: Batteries form the heart of your solar system, representing the largest investment. In my setup, I allocated $2,960 (41.6%) for eight 12V 200AH LiFePo4 batteries with built-in Battery Management Systems (BMS). While budget options exist, battery quality directly impacts system reliability and longevity - making this an area where cutting costs can prove expensive in the long run. Goldenmate Batteries: 12V 200AH battery I went with Goldenmate batteries, which offer grade A LiFePo4 cells in excellent protective containers. You can get 15% off with my referral code. While I chose Goldenmate for their good value / price ratio, several other reputable manufacturers offer quality LiFePo4 batteries: Brand Price Range Notable Features Battle Born $$$$ • Made in USA• 10-year warranty• Excellent customer service SOK $$ • Active BMS• Good price/performance• Growing community support BigBattery $$$ • UL certified• Multiple form factors• Commercial grade options JITA $$ • Budget friendly• Basic but reliable• Popular for DIY builds The key is finding the right balance between cost, reliability, and support for your needs. While premium brands like Battle Born offer superior warranties and service, mid-range options can provide excellent value without compromising essential features. For solar panels, I took an unconventional but cost-effective approach. Rather than purchasing new panels, I invested $1,200 (16.9%) in used 245W-250W panels sourced locally. This decision offered compelling advantages: Benefits of Used Panels: Dramatic cost savings (50-75% below retail) Zero shipping expenses Immediate availability Environmental sustainability Considerations: Efficiency loss of 10-15% from age Possible micro-fractures from thermal cycling No manufacturer warranty For those with adequate installation space, used panels present an attractive value proposition. The slight reduction in efficiency can be offset by installing additional panels while maintaining significant cost savings. My system uses a 4000W 48V inverter, representing $380 (5.3%) of the total investment. While a smaller expense comparatively, inverter selection requires careful consideration of: Battery voltage compatibility Peak power requirements Output waveform quality Future expansion needs The remaining investment covers essential system elements: Solar panel mounting hardware ($1,056 - 14.9%) Smart charge controller ($600 - 8.4%) Automatic transfer switch ($180 - 2.5%) Battery monitoring system ($110 - 1.5%) Safety equipment and wiring (~8%) My complete 20KWH system includes: 48V 200AH Lithium Iron Phosphate batteries (8 x 12V 200AH in series) 24 x 245W-250W panels (3920W total) 16 x YL245P-29b 8 x Hyundai HiS-S250MG 48V, 4000W inverter with 8000W surge (pure sine wave 110V/120V) 4 circuit transfer switch (15A/120V per circuit) Powers refrigerator, entertainment system, 2 AC units, master outlets Planning 5th switch for home office Note on 240V: This system handles 120V only. For 240V needs, consider these split phase inverters: WZRELB 4000W 48V PowMr 5000W Solar Inverter POWLAND 5000W Solar Hybrid You can view the complete materials list here: Parameter YL245P-29b Hyundai HiS-S250MG Power Output (Pmax) 245 W 250 W Power Output Tolerances ±5% ±3% Module Efficiency 15.0% 15.37% Voltage at Pmax (Vmp) 29.6 V 30.6 V Current at Pmax (Imp) 8.28 A 8.17 A Open-circuit Voltage (Voc) 37.5 V 37.8 V Short-circuit Current (Isc) 8.83 A 8.72 A Parameter YL245P-29b Hyundai HiS-S250MG Dimensions (L / W / H) 64.96 in x 38.98 in x 1.57 in (1650 mm x 990 mm x 40 mm) 65.0 in x 39.0 in x 1.57 in (1650 mm x 990 mm x 40 mm) Weight 40.8 lbs (18.5 kg) 41.9 lbs (19.0 kg) Here are several key ways to save money while maintaining core functionality: I spent $1,055.88 on solar panel tilt mounts and stands, which are aluminum rails that the solar panels mount to. These help optimize solar charge and efficiency over the long run by making sure the panels face south and at the optimal angle. The prebuilt aluminum rails cost around $40 per stand per panel. You have several options to reduce this cost: Lay panels flat (simplest but takes ~15% efficiency hit) DIY tilting mounts using wood/metal Use cinderblocks for basic elevation If going the DIY route, make sure your build is robust against inclement weather. The general consensus is that optimizing your solar panel tilt results in a 15% efficiency gain on average, depending on your seasonal tilt needs. But if you're skilled with DIY construction, you could save over $1000 here while still getting most of the benefits. If you are limited on space, it could be easier to opt out of any solar stands, but it is an investment that pays dividends. Use this calculator to determine your optimal panel angle based on location: https://www.youtube.com/embed/mUpTRtO4eN0 In my setup, I split my inverter, charge controller, fuses, battery disconnect, and battery monitors into their own separate components. This ensures greater modularity so that I can easily replace components in the future for whatever reason. I also spent around $900 for all of this. While all-in-one solutions can save you $200-$300, they come with some additional requirements. You'll need to buy: Outlet boxes - Southwire MSB1G for organized management Circuit breakers - AC Miniature Circuit Breaker going to outlets for safety Outlets - Leviton T5320-WMP to deliver power Additionally, if one of these hybrid solar inverters stops working for any reason, you better hope you are still under warranty, or you'll have to shell out another $600-$700 for a system, which essentially makes its not worth the price anymore. You can also consider going up the supply chain for your batteries to save money. Although this may not be as cost effective anymore now in 2024 due to Lithium surplus in the market. In the past, pre-packaged LiFePo4 batteries with BMS (battery management systems) built-in would cost a premium compared to buying LiFePo4 batteries in bulk without the BMS or packaging. Doing your own LiFePo4 battery pack would involve buying individual 3V Lithium battery cells most likely from China via Alibaba, taping them together into larger sections in series and parallel. It honestly isn't terribly hard work, but given the decreasing $ / KW premium on the market, you can get a good pre-packaged LiFePo4 battery now for the same cost as the raw battery cells, and in my opinion, it isn't worth the hassle. https://www.youtube.com/embed/TjrtqBTlO6w?start=314 Another option that can be cheaper is buying used battery packs from electric vehicles. Many of these electric vehicles like Teslas have incredible battery packs that are around the 60KWH range +/- depending on the specific configuration. Many times, you can get a great deal on these used battery packs because it takes work to prepare them for home use. I will warn you that this option may not be as DIY friendly due to the larger battery pack and electronics, so I wouldn't recommend unless you are very knowledgeable and confident in your skills. However, if you are able to acquire one and have the technical know-how, you can easily divvy up the battery pack into separate cells, or just use the massive 60KWH system for your home. https://www.youtube.com/embed/tatCDbgmnxc Building a DIY solar backup system is a significant undertaking that requires careful planning, research, and investment. While my complete 20KWH system cost around $7,000, I've shown how you can build a robust 10KWH system for under $5,000 by: Starting with 4 batteries instead of 8 ($1,400 savings) Skipping or DIY-ing the solar panel stands ($1,000+ savings) Considering all-in-one inverter solutions ($200-300 savings) Remember that this system is not just about saving money - it's about energy independence and peace of mind during power outages. The modular approach I took may cost more upfront but offers key advantages: Easy expansion (each 2.5KWH battery addition costs ~$350) Component-level replacement instead of whole-system replacement Flexibility to upgrade individual parts as technology improves Better redundancy during component failures Whether you follow my exact build or opt for a more budget-friendly version, focus on these core principles: Always prioritize safety in your electrical design Size your system based on actual power needs Choose quality batteries - they're the foundation of reliability Consider future expansion in your initial setup Document your build for easier maintenance I encourage you to carefully consider your power needs, budget constraints, and technical comfort level when planning your build. Start small if needed - you can always expand the system later as your needs and expertise grow. The most important thing is to build a system that you understand and can maintain confidently. For those interested in learning more, I've provided detailed calculators and resources throughout this guide to help you: Calculate optimal solar panel positioning Determine your daily power requirements Size your battery bank appropriately Select compatible components Stay safe, and happy building!